CSRF – Security Acronyms explained

This article is part of a series on security acronyms every Django developer should know.

CSRF stands for Cross-Site request forgery and describes a certain kind of attack on a web application. Cross-Site request forgery is quite a mouthful, so I’m going to use the acronym CSRF for the rest of the article.

How do you use this acronym correctly?

Fellow software developers can be quite picky when it comes to the right use of words, so let’s look at some examples how you would use that acronym correctly.

- Your site is vulnerable to CSRF attacks.

- I have implemented CSRF protection for our site.

- The hacker used CSRF to empty the bank account.

- How do I fix the error “CSRF token missing or incorrect”?

Hopefully, you will never have to tell your boss the third one in real-life!

How does a CSRF attack work?

In a CSRF attack, a website forces the visitor’s browser to perform a request to another website that causes some kind of change.

Let’s say you are building a Twitter clone hosted on https://a/. When a user is logged in, he can enter a status update into a form. When that form is POSTed to https://a/status/, the corresponding view stores the status update in the database and other users can see it on the user’s page, e.g. https://a/daniel/. Now, Django comes with built-in CSRF protection, but you couldn’t get it to work and were in a rush, so you disabled it.

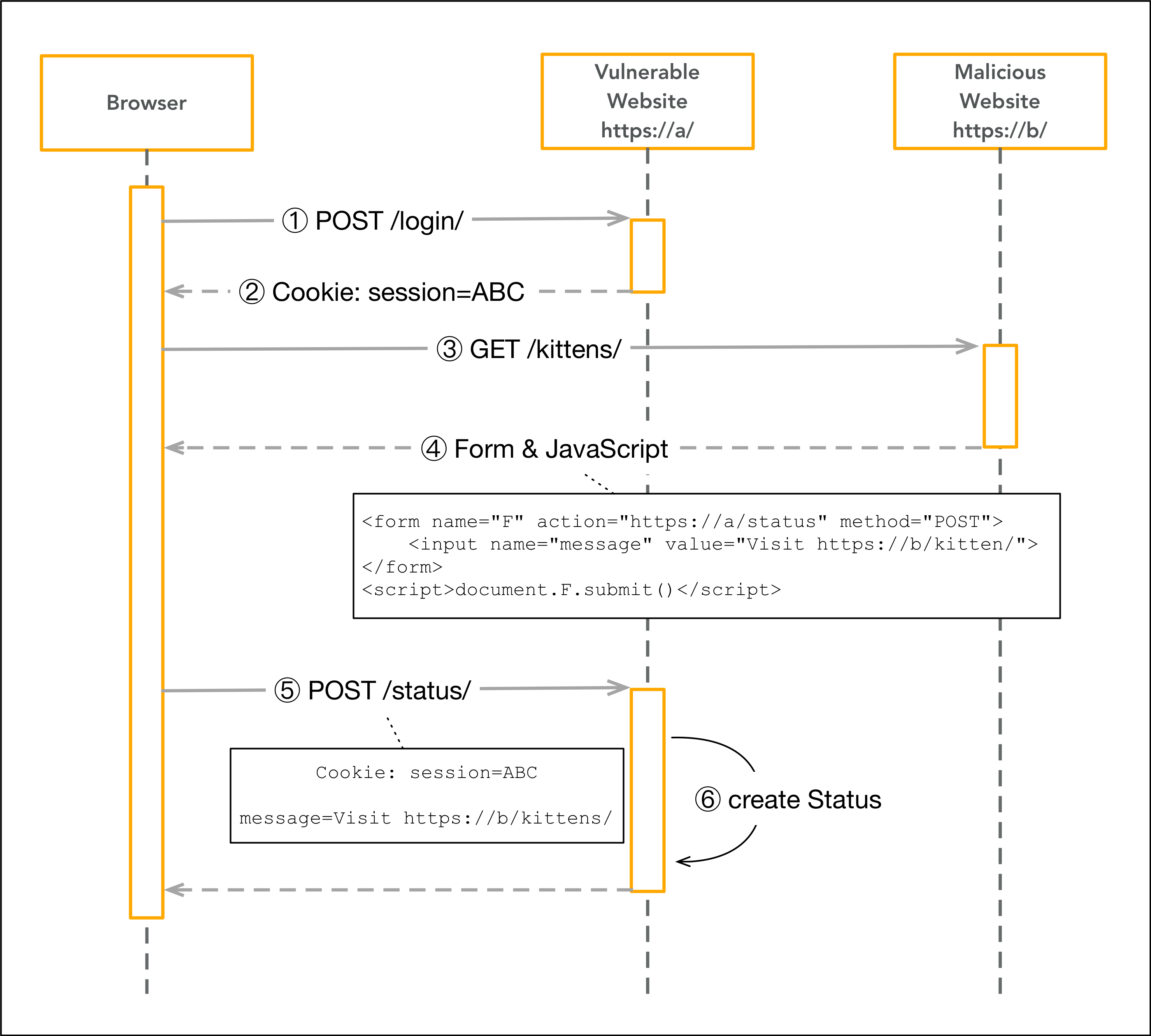

A CSRF attack unfolds like this:

- The user logs into your site https://a.

- Your server returns a session cookie.

- An attacker tricks the user into visiting a site he controls, e.g. https://b/kittens/. You can’t blame the user, who doesn’t like kittens?

- The attacker’s site returns a form that has https://a/status/ as action and some JavaScript that automatically submits the form.

- The user’s browser executes the JavaScript and

POSTs the form to your server. This post request contains the user’s session cookies and is therefore authenticated. - Your server receives the

POSTrequest with the spam message crafted by the attacker. It has no way to determine that it was not triggered by the user and creates a status with the spam message.

Live Demo

If you want to see this vulnerability in action, visit https://csrf-example.herokuapp.com. Don’t worry, the page is harmless and won’t give your computer a virus or something. You can find the source code for this application on Github.

There you will find a really simple Twitter clone called Chirper. It is written in Django and has been intentionally made vulnerable to CSRF attacks.

Click the button on the homepage to create a user account and post a status update. Then go look at a cute kitten (with JavaScript enabled).

After a few seconds, the kitten will disappear and you will find yourself back on your Chirper profile, where the malicious kitten site has posted a message in your name!

In this example, the vulnerability might just cause an annoyance for the user and the attack is really easy to spot. But the attack could be a lot sneakier and result in much more severe consequences. Consider a vulnerable webpage that is used to:

- delete an account

- transfer money (or crypto currencies)

- upload files to an intranet page

- control a hardware device, like an internet router, an alarm system or a power plant

Note that a site can be attacked even if it is not available on the public internet. All that matters is that the user’s browser can reach the site. “It’s just an internal site” is not a valid excuse for not implementing CSRF protection!

Protecting against CSRF attack

We’ve only looked at forms and POST requests so far. Does that mean that a view that only handles GET requests is immune against this kind of attack? It should be, but that takes some effort on your side.

Let’s talk about HTTP methods real quick. The HTTP method GET is considered a “safe” request method, meaning that requesting a URL with GET is not expected to result in any changes on the server and shouldn’t cause any harm.

Other, less common HTTP methods that are considered safe are HEAD, OPTIONS and TRACE.

A view handling a GET, HEAD, OPTIONS and TRACE request should never perform any create, update or delete operations. Some secondary changes, like updating a view counter or a “last seen” timestamp, might be acceptable.

Alright, safe methods, no changes. But what about the unsafe methods POST, PUT, DELETE? These are expected to result in changes on the server and need to be protected against CSRF attacks.

Luckily, Django comes with built-in CSRF protection. Using it is quite simple:

- Add the

django.middleware.csrf.CsrfViewMiddlewareto theMIDDLEWAREsetting. - In your templates, add the

csrf_tokentag to any form that uses the POST method. - Use the

render()or use aRequestContextto render the template

Using it with AJAX is a bit more complicated, but the Django CSRF documentation has an extensive section on AJAX.

How does Django’s CSRF protection mechanism work?

Simply speaking, the CSRF middle sets a cookie with a secret value and the {% csrf_token %} tag adds the same value in a hidden field. When the form is submitted, the browser sends the cookie and the hidden field. The middleware then checks that the value in the form matches the value in the cookie. If the values match, the request is processed, otherwise, it is rejected with an HTTP 403 response.

Why does this prevent the attack? Because an attacker cannot read anything from your site, so he would have to guess the value of the CSRF token.

For a more detailed explanation how the CSRF protection in Django works, I encourage you to check out the explanation in the official Django documentation.

Troubleshooting CSRF

Django’s CSRF protection involves a couple of moving parts and thus comes with multiple points of failure. Fundamentally, there are two ways the CSRF protection can fail:

- It can prohibit requests that should be allowed.

- It can allow requests that should be prohibited.

The first case is probably more common, but it is also pretty easy to spot during development because it usually results in a response with status 403 Forbidden and the message “CSRF verification failed”.

Trying to cover everything that can go wrong goes beyond the scope of this article, but I will give you some ideas that hopefully point you in the right direction.

- Does your template contain the

{% csrf_token %}tag? - Does your view use

render()orRequestContextto render the template? - Does your AJAX request send the token, either as data or header?

- Does loading your page cause any 404 errors that set a new CSRF cookie? (That’s a tricky one to spot!)

There is one technical detail I want to dive into. Before Django 1.10, the CSRF token was a secret that stayed the same most of the time. This made it easy to debug problems: if the request has a different token value in the body data than in the cookie, there was something wrong.

Starting with Django 1.10, the secret in the CSRF token is scrambled with a random value on each request. That means that two different tokens don’t necessarily contain different secrets.

But what about requests that should be prohibited, but aren’t? For this case, we have to ask ourselves:

How does a Django project become vulnerable to CSRF attacks?

When you create a new Django project with django-admin.py startproject, it comes with a settings file that has CSRF protection enabled. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t quite a few ways how you can end up with unprotected views that are vulnerable to CSRF attacks. Here are a few examples:

Not using CSRF middleware

If you don’t have the CSRF middleware in your MIDDLEWARE setting, your site is not protected by default. It is easy to unintentionally end up without the middleware, e.g. by:

- Changing the MIDDLEWARE setting and unintentionally removing it.

- Starting with a custom project template that comes without a middleware.

- Turning an API-only project which didn’t use cookie-based authentication and thus didn’t require CSRF protection into a full-blown website which does.

If you intentionally removed the middleware, make sure to apply the csrf_protect decorator to all views that need CSRF protection. However, it would be safer to add the middleware and use the csrf_exempt decorator on views that definitely do not need CSRF protection.

Using the csrf_exempt decorator

The csrf_exempt decorator does exactly what the name implies: it exempts the view from CSRF protection. Think twice before you apply this decorator to a view or before you modify a view that uses it.

Performing changes on GET requests or other safe HTTP methods

As we learned earlier, GET, HEAD, OPTIONS and TRACE are considered safe HTTP methods and should not perform any changes. Make sure that you enforce this on the server side. It is not enough to add method="POST" to the form, you have to check the method in your view.

To restrict a view to certain HTTP methods, e.g. POST, you can either check that request.method == 'POST' or use the require_http_methods decorator.

# This view performs changes and accepts all HTTP methods

# and is therefore vulnerable to CSRF attacks

def unsafe_delete_view(request, pk):

obj = get_object_or_404(MyModel, pk=pk)

obj.delete()

return HttpResponse('ok')

from django.views.decorators.http import require_http_methods

# This view only allows POST requests

# If you use the CSRF middleware, it is save

@require_http_methods(["POST"])

def better_delete_view(request, pk):

obj = get_object_or_404(MyModel, pk=pk)

obj.delete()

return HttpResponse('ok')

If you find yourself doing any of the above things or come across them in a code review, this should get your spidey senses tingling. Can you come up with more? Leave a comment!

Summing up

We have covered quite a bit in this article. If you made it this far, you should be able to answer these questions:

- What does the acronym CSRF mean?

- How does a CSRF attack work?

- How does Django’s CSRF protection work?

- How can Django’s CSRF protection break?

This wraps up the first article on security acronyms every Django developer should know. If anything remains unclear, leave a comment below or get in touch on Twitter or via Email.

The next acronym I will look at is XSS. Luckily, Django sites are not affected by it. Or are they? Check out the next post in this series to find out.

One thought on “CSRF – Security Acronyms explained”